Congress’s Proposed Revisions to Patent Eligibility Leave Critical Questions Unanswered

Senators Chris Coons (D-Del.) and Thom Tillis (R-N.C.), the ranking member and chairman, respectively, of the Senate Judiciary Subcommittee on Intellectual Property, have released a proposed framework for an overhaul of the statutory definition of patent-eligible subject matter. A parallel version has also been released in the House of Representatives by Reps. Doug Collins (R-Ga.), Hank Johnson (D-Ga.), and Steve Strivers (R-Ohio).

Five years ago, the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in Alice Corp. Pty. Ltd. v. CLS Bank International, 134 S. Ct. 2347 (2014) invalidated as ineligible patent claims drawn to a computer-implemented scheme for mitigating financial risk, and provided broad guidance as to the test for eligibility. Since then, lower courts have been flooded by motions to invalidate patent claims on similar grounds. However, as described by the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office’s 2019 Revised Patent Subject Matter Eligibility Guidance, “[p]roperly applying the [eligibility] test in a consistent manner has proven to be difficult, and has caused uncertainty in this area of the law.” This has led to increasing calls from industry groups and stakeholders for standardization among the various methodologies currently employed by the patent office and the courts.

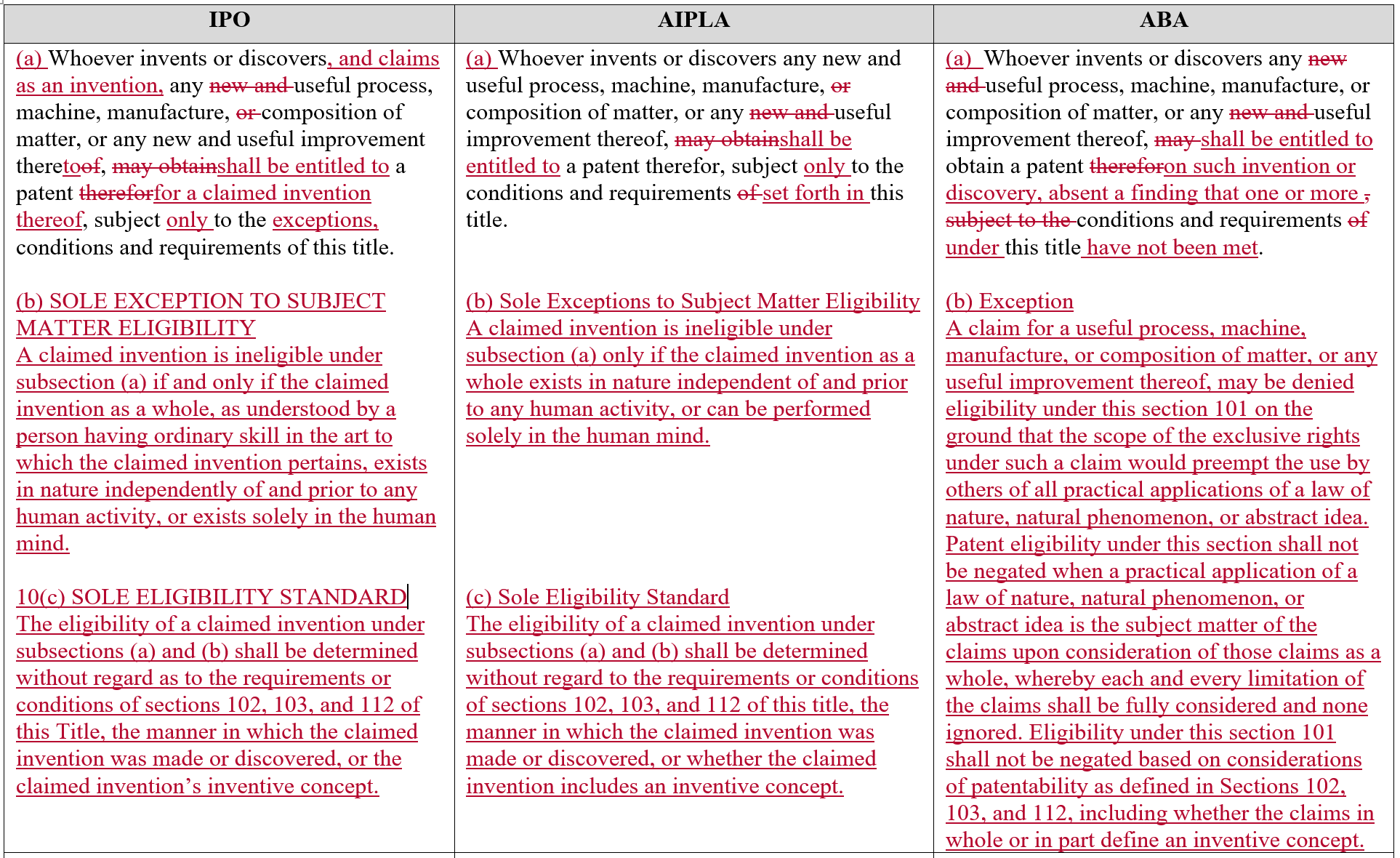

For those familiar with the legislative proposals submitted by the American Bar Association (ABA), Intellectual Property Owners Association (IPO), or the American Intellectual Property Law Association (AIPLA) over the past year, the framework proposed by Sens. Coons and Tillis will look familiar, although there are three significant differences:

First, the congressional proposal expands the categories of exceptions to eligibility. Both the IPO and AIPLA proposals limit the exceptions to (a) subject matter existing in nature independent of human activity, and (b) subject matter existing solely in the human mind. The ABA proposal limits the exceptions even further, to only subject matter that fully preempts the use by others of all practical applications of a law of nature or abstract idea. The congressional proposal, by contrast, does not require preemption and instead carves out two additional exceptions: subject matter directed to a “pure mathematical formula,” and subject matter directed to “economic or commercial principles.”

Second, the congressional proposal does not appear to do away with inventive concept, the second step in the Mayo/Alice test for eligibility, as all three of the other proposals do. While all three of the industry group proposals provide that eligibility shall be considered independently of sections 102, 103, 112, or the claimed invention’s inventive concept, the congressional proposal does not include the reference to inventive concept at all. This may indicate that the senate proposal is expected to operate similarly to the 2019 USPTO Guidance, which maintains a separate “inventive step” inquiry if the abstract idea step (Mayo/Alice step one) is answered in the affirmative. The deference to the USPTO guidance is further shown by the third difference between the congressional proposal and the industry group proposals:

The congressional framework adds a “practical application” evaluation that is absent from any of the other three proposals. While no particulars are given with regard to what that requirement might entail in the senate proposal, it matches language used in the USPTO guidance, which instructs examiners to allow claims directed to subject matter otherwise covered by an exception if any element of the subject matter is integrated into a “practical application” of the subject matter.

Like Senator Coons’ recent proposal to gut the PTAB’s authority through his STRONGER Patents Act, although not to the same degree, this proposal weighs in favor of patent owners to the detriment of challengers. And while that may be appropriate given the disconnect between an issued patent’s statutory presumption of validity and the 60% of district court eligibility challenges (a majority at the pleadings stage) that resulted in invalidation, it is likely to be a source of frustration to the technology industry and other frequent targets of spurious patent infringement suits. This proposal on its face defangs one of the more effective defenses against non-practicing entities, although much will depend on the particulars of the practical application test, including the metes and bounds of its application to computer methods.

For now, it seems likely that support for this proposal will break down along usual industry lines, with the biotech and pharmaceutical industries lining up in favor and the tech industry against, as congress appears poised to put this bill on the fast track.